PORTRET z HISTORIĄ Maurice Sendak

- Czesław Czapliński

- 14 gru 2025

- 21 minut(y) czytania

Maurice Sendak (/ˈsɛndæk/; 10 czerwca 1928 – 8 maja 2012) był amerykańskim autorem i ilustratorem książek dla dzieci. Urodził się w rodzinie polskich Żydów, a na jego dzieciństwo silnie wpłynęła śmierć wielu członków rodziny podczas Holokaustu. Sendak ilustrował zarówno własne książki, jak i dzieła innych autorów, m.in. serię Little Bearautorstwa Else Holmelund Minarik. Międzynarodowe uznanie przyniosła mu książka Where the Wild Things Are (1963), pierwsza część trylogii, po której ukazały się In the Night Kitchen (1970) oraz Outside Over There (1981). Projektował również scenografie do oper, w tym do Czarodziejskiego fletu Mozarta.

W 1987 roku Sendak był bohaterem filmu dokumentalnego z cyklu American Masters pt. Mon Cher Papa. W 1996 roku otrzymał Narodowy Medal Sztuki (National Medal of Arts). Jak napisała Margalit Fox, Sendak — „najważniejszy artysta książki dziecięcej XX wieku” — „wyrwał książkę obrazkową z bezpiecznego, wysterylizowanego świata dziecięcego pokoju i zanurzył ją w mrocznych, przerażających i zarazem zachwycająco pięknych zakamarkach ludzkiej psychiki”.

Sendak urodził się 10 czerwca 1928 roku na Brooklynie w Nowym Jorku jako syn polsko-żydowskich imigrantów: Sadie (z domu Schindler) i Philipa Sendaka, krawca. Maurice wspominał swoje dzieciństwo jako „straszne”, ze względu na śmierć członków dalszej rodziny podczas Holokaustu, co już w młodym wieku uświadomiło mu istnienie śmierci. Jego miłość do książek narodziła się w dzieciństwie, gdy z powodu problemów zdrowotnych był przykuty do łóżka. Był „zafascynowany Myszką Miki (która powstała w roku jego urodzenia), amerykańskimi komiksami oraz jasnymi światłami Manhattanu”. W wieku 12 lat postanowił zostać ilustratorem po obejrzeniu filmu Walta Disneya Fantazja(1940).

Maurice był najmłodszym z trójki rodzeństwa, urodzonym pięć lat po Jacku Sendaku i dziewięć lat po Natalie Sendak. Jack również został autorem książek dla dzieci, z których dwie zostały zilustrowane przez Maurice’a w latach 50. W 2011 roku Maurice pracował nad książką o nosach i przypisywał swoją sympatię do tego organu bratu Jackowi, który — zdaniem Sendaka — miał wyjątkowo piękny nos.

W nowojorskiej Art Students League uczęszczał na zajęcia prowadzone przez Johna Grotha, który nauczył go „poczucia ogromnego potencjału ruchu i życia w ilustracji… Sam pokazywał, ile radości może sprawiać tworzenie”.

Maurice Sendak rozpoczął swoją karierę zawodową w 1947 roku, ilustrując popularnonaukową książkę Atomics For the Millions. Jednym z jego pierwszych zleceń, gdy miał 20 lat, było tworzenie wystaw okiennych dla sklepu z zabawkami FAO Schwarz. Kupująca książki dziecięce w tym sklepie przedstawiła go Ursuli Nordstrom, redaktorce literatury dziecięcej w wydawnictwie Harper & Row, która później redagowała m.in. Charlotte’s Web (1952) E.B. White’a oraz Harriet the Spy (1964) Louise Fitzhugh. Dzięki temu Sendak otrzymał swoje pierwsze zlecenie ilustratorskie do książki dziecięcej — The Wonderful Farm (1951) Marcela Aymé. Jego prace pojawiły się w ośmiu książkach Ruth Krauss, w tym w A Hole is to Dig (1952), która przyniosła jego ilustracjom szerokie uznanie. Ilustrował także pierwszych pięć tomów serii Little Bear autorstwa Else Holmelund Minarik. Fundacja Maurice’a Sendaka wskazuje Krauss, Nordstrom oraz Crocketta Johnsona jako jego mentorów. Jako samodzielny autor zadebiutował książką Kenny’s Window (1956). W 1962 roku opublikował Nutshell Library, zbiór obejmujący Alligators All Around, One Was Johnny, Pierre oraz Chicken Soup With Rice. O Ursuli Nordstrom mówił: „Traktowała mnie jak kwiat w szklarni — podlewała mnie przez dziesięć lat i starannie dobierała dzieła, które stały się moim stałym zapleczem wydawniczym i źródłem utrzymania”.

Międzynarodową sławę Sendak zdobył po napisaniu i zilustrowaniu książki Where the Wild Things Are (1963), redagowanej przez Nordstrom. Opowiada ona o Maxie, chłopcu, który „wścieka się na matkę za to, że został wysłany do łóżka bez kolacji”. Przedstawienie kłastych potworów wzbudziło niepokój niektórych rodziców po publikacji książki, gdyż postacie miały dość groteskowy wygląd. Sendak wyjaśniał, że tytuł pochodzi od jidyszowego zwrotu vilde chaya, czyli „dzika bestia”: „To coś, co niemal każdy żydowski rodzic mówi do swojego dziecka: ‘Zachowujesz się jak vilde chaya! Przestań!’”. Książka zdobyła Medal Caldecotta, uważany za najwyższe wyróżnienie dla książek obrazkowych w Stanach Zjednoczonych. Humphrey Carpenter i Mari Prichard pisali, że „powszechnie uznaje się ją za dzieło bezkonkurencyjne w eksplorowaniu świata dziecięcej fantazji i jego relacji z rzeczywistością”. Została zaadaptowana jako opera przez Olivera Knussena oraz jako film przez Spike’a Jonze’a.

Sendak później przytaczał reakcję jednego z fanów:„Mały chłopiec przysłał mi uroczą kartkę z rysunkiem. Bardzo ją pokochałem. Odpowiadam na wszystkie listy od dzieci — czasem bardzo pospiesznie — ale nad tym zatrzymałem się dłużej. Odesłałem mu kartkę i narysowałem na niej Dzika Stwora. Napisałem: ‘Drogi Jimie: bardzo spodobała mi się twoja kartka’. Potem dostałem list od jego mamy, w którym napisała: ‘Jim tak bardzo pokochał twoją kartkę, że ją zjadł’. Dla mnie był to jeden z największych komplementów, jakie kiedykolwiek otrzymałem. Nie obchodziło go, że to oryginalny rysunek Maurice’a Sendaka. Zobaczył ją, pokochał — i zjadł.”

Sendak zilustrował The Bat Poet (1964), książkę dla dzieci autorstwa Randalla Jarrella. Gdy zobaczył na biurku redaktora w wydawnictwie Harper & Row maszynopis Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories, pierwszej książki dziecięcej Isaaca Bashevisa Singera, zaproponował, że ją zilustruje. Książka została po raz pierwszy opublikowana w 1966 roku i otrzymała wyróżnienie Newbery Honor. Sendak był entuzjastycznie nastawiony do tej współpracy. Z przekąsem zauważył kiedyś, że jego rodzice „wreszcie” byli pod wrażeniem najmłodszego dziecka, gdy współpracował z Singerem.

Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More To Life (1967), zainspirowana psem Sendaka, Jennie, była jego ulubioną spośród własnych książek. Nazywał ją „moim requiem dla [Jennie] — niesentymentalnym, wręcz komicznym requiem dla bystrego, upartego, lojalnego i kochanego stworzenia, którego wszechogarniającą pasją było jedzenie”.

In the Night Kitchen (1970) to „dalsza eksploracja świata dziecięcej fantazji chłopca, tym razem ściśle oparta na wspomnieniach Sendaka z dzieciństwa w Nowym Jorku”. Fox pisze, że „ogromne, płaskie, jaskrawo kolorowe ilustracje” są „hołdem dla Nowego Jorku z dzieciństwa pana Sendaka, przywołującym filmy i komiksy z lat 30., które kochał przez całe życie”. Sam Sendak wyjaśniał: „To był hołd dla wszystkiego, co kochałem: Nowego Jorku, imigrantów, Żydów, Laurel i Hardy’ego, Myszki Miki, King Konga, kina. Wrzuciłem to wszystko do jednej zwariowanej książki”. Książka była często cenzurowana ze względu na rysunki przedstawiające nagiego chłopca paradowującego w trakcie opowieści. Była kwestionowana w kilku stanach USA, m.in. w Illinois, New Jersey, Minnesocie i Teksasie. In the Night Kitchenregularnie pojawia się na liście Amerykańskiego Stowarzyszenia Bibliotek „często kwestionowanych i zakazywanych książek”. Zajęła 21. miejsce na liście „100 najczęściej kwestionowanych książek lat 1990–1999”.

Outside Over There (1981) opowiada historię dziewczynki o imieniu Ida oraz jej zazdrości wobec rodzeństwa i poczucia odpowiedzialności. Ojciec jest nieobecny, więc Ida musi opiekować się młodszą siostrą, co bardzo ją irytuje. Siostra zostaje porwana przez gobliny, a Ida musi wyruszyć w magiczną podróż, by ją uratować. Początkowo nie jest szczególnie chętna do odnalezienia siostry i niemal ją mija, pochłonięta magią wyprawy. Ostatecznie jednak ratuje siostrę, niszczy gobliny i wraca do domu, zdecydowana opiekować się nią aż do powrotu ojca. Ta opowieść ratunkowa zawiera ilustrację drabiny wystającej z okna domu, która — według jednego z doniesień — była inspirowana miejscem zbrodni w sprawie porwania dziecka Lindberghów, „co przerażało Sendaka w dzieciństwie”. Carpenter i Prichard piszą: „Ciemniejsza tematycznie niż Where the Wild Things Are i In the Night Kitchen, została opublikowana zarówno na listach książek dla dorosłych, jak i dla dzieci, i ukazywała wyraźną zmianę stylu ilustracyjnego, całkowicie odchodzącą od manier komiksowych, które były zawsze częściowo obecne w dwóch pozostałych książkach”. Sendak umieścił w niej także cameo jednego ze swoich ulubionych kompozytorów — Wolfganga Amadeusa Mozarta. Zbiór jego esejów i wykładów ukazał się jako Caldecott & Co.: Notes on Books and Pictures (1988).

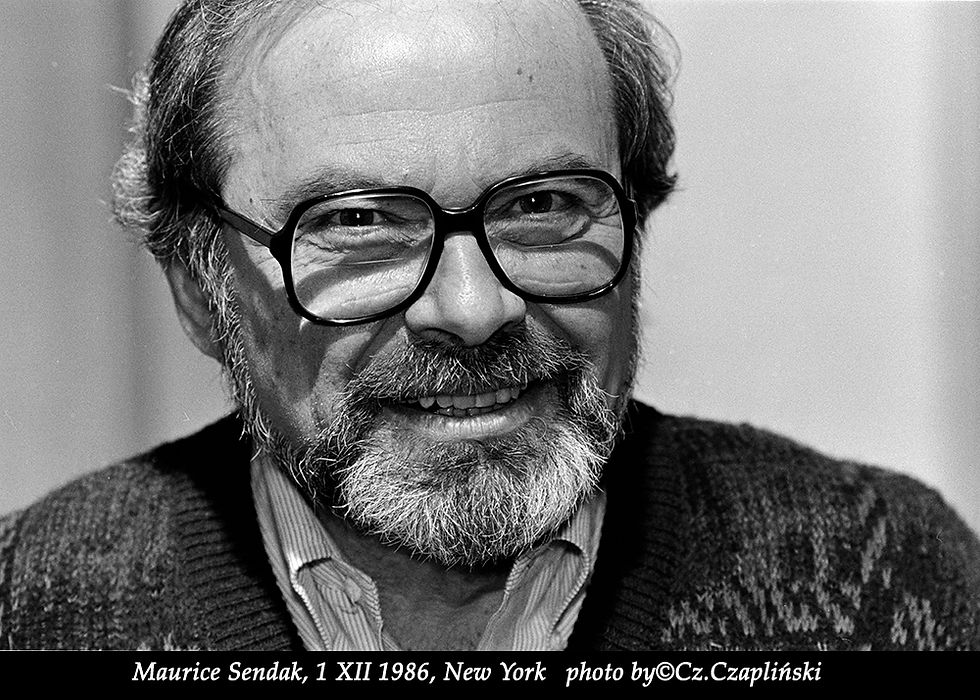

„…Maurice Bernard Sendaka spotkałem i fotografowałem 1 grudnia 1986 r. w Nowym Jorku, kiedy wyszła jego kolejna książka „The Bee-Man of Orn” napisana przez Frank Richard Stocktona, do której ilustracje zrobił Maurice Sendak. Muszę powiedzieć, że Sendak zrobił na mnie duże wrażenie, dlatego zdecydowałem się na dużą serię zdjęć…” – Czesław Czapliński

W 1993 roku Sendak opublikował We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy, książkę poświęconą kryzysowi AIDS. Później, w latach 90., zwrócił się do dramaturga Tony’ego Kushnera z prośbą o napisanie nowej anglojęzycznej wersji opery Brundibár czeskiego kompozytora Hansa Krásy — dzieła związanego z Holokaustem, które było wykonywane przez dzieci w obozie koncentracyjnym Theresienstadt. Kushner napisał tekst do ilustrowanej przez Sendaka książki o tym samym tytule, opublikowanej w 2003 roku. Została ona uznana za jedną z 10 najlepiej zilustrowanych książek 2003 roku według The New York Times Book Review. Gregory Maguire napisał: „W karierze obejmującej 50 lat i więcej, jak u Sendaka, muszą pojawić się słabsze dzieła. Brundibár nie jest słabszy od żadnego z nich”.

W 2011 roku Sendak zaadaptował swój krótki film z Ulicy Sezamkowej, Bumble Ardy, na książkę dla dzieci — swoją pierwszą od ponad trzydziestu lat i ostatecznie ostatnią opublikowaną za jego życia. My Brother’s Book (2013) ukazała się już pośmiertnie. Dwight Garner napisał: „Jej uroki są stonowane i refleksyjne. Ta moralna przypowieść może znaleźć największe grono odbiorców wśród dorosłych”.

Sendak był jednym z pierwszych członków Narodowej Rady Doradczej Children’s Television Workshop w fazie rozwoju serialu telewizyjnego Sesame Street. Stworzył dla tej serii dwie animowane opowieści: Bumble Ardy — animowaną sekwencję, w której głosu tytułowemu bohaterowi użyczył Jim Henson — oraz Seven Monsters. Później Sendak zaadaptował Seven Monsters do książki Seven Little Monsters, która z kolei doczekała się animowanej adaptacji telewizyjnej.

Sendak napisał animowany musical Really Rosie, z udziałem wokalnym Carole King, wyemitowany w 1975 roku. Jest on dostępny na wideo (zazwyczaj jako część kompilacji jego prac), a piosenki ukazały się również na osobnym albumie. Był także autorem sekwencji otwierającej Simple Gifts — świąteczny zbiór sześciu animowanych filmów krótkometrażowych emitowanych w PBS w 1977 roku, a później wydanych na VHS w 1993. W 1979 roku zaadaptował Where the Wild Things Are na potrzeby sceny teatralnej.

Ponadto projektował scenografie i kostiumy do wielu oper i baletów, w tym do nagradzanej produkcji Dziadka do orzechów Czajkowskiego w wykonaniu Pacific Northwest Ballet (1983), spektakli Glyndebourne Festival Opera: Miłość do trzech pomarańczy Prokofiewa (1982), Dziecko i czary oraz Godzina hiszpańska Ravela (1987), a także adaptacji Knussena książki Sendaka Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life (1985). Projektował również scenografie dla Houston Grand Opera do Czarodziejskiego fletu Mozarta (1981) i Jasia i Małgosi Humperdincka (1997), dla Los Angeles County Music Center do Idomenea Mozarta (1990), dla New York City Opera do Przebiegłej lisiczkiJanáčka (1981) oraz dla Lyric Opera of Kansas City do Gęsi z Kairu Mozarta (1982).

W 2003 roku Chicago Opera Theatre wystawił adaptację Brundibára autorstwa Sendaka i Kushnera. W 2005 roku Berkeley Repertory Theatre — we współpracy z Yale Repertory Theatre oraz nowojorskim New Victory Theater na Broadwayu — zaprezentował gruntownie przerobioną wersję tej adaptacji. W 2004 roku Sendak współpracował z bostońską Shirim Klezmer Orchestra przy projekcie Pincus and the Pig: A Klezmer Tale. Ta klezmerska wersja najsłynniejszej muzycznej opowieści Prokofiewa dla dzieci, Piotruś i wilk, miała Maurice’a Sendaka w roli narratora; był on również autorem ilustracji na okładkę.

Margalit Fox pisała, że „jego sztuka zdobiła teksty innych wybitnych autorów piszących zarówno dla dzieci, jak i dorosłych, w tym Hansa Christiana Andersena, Lwa Tołstoja, Hermana Melville’a, Williama Blake’a oraz Isaaca Bashevisa Singera”.

W artykule z września 2008 roku opublikowanym w The New York Times Sendak ujawnił, że jest gejem i że przez 50 lat mieszkał ze swoim partnerem, psychoanalitykiem Eugene’em Davidem Glynnen (25 lutego 1926 – 15 maja 2007), aż do jego śmierci w maju 2007 roku. Wyznając, że nigdy nie powiedział o tym rodzicom, stwierdził: „Chciałem tylko być heteroseksualny, żeby moi rodzice mogli być szczęśliwi. Oni nigdy, przenigdy się nie dowiedzieli”. Związek Sendaka z Glynnen był wcześniej wspominany przez innych autorów (m.in. Tony’ego Kushnera w 2003 roku), a w nekrologu Glynna z 2007 roku Sendak został określony jako jego „partner od pięćdziesięciu lat”. Po śmierci partnera Sendak przekazał milion dolarów na rzecz Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services ku pamięci Glynna, który leczył tam młodych ludzi. Środki te przeznaczono na klinikę, która miała nosić imię Glynna.

Sendak był ateistą. W wywiadzie z 2011 roku powiedział, że nie wierzy w Boga, dodając, iż religia i wiara „musiały bardzo ułatwiać życie [niektórym jego religijnym przyjaciołom]. Nam, niewierzącym, jest trudniej”.

Na początku lat 60. Sendak mieszkał w piwnicznym mieszkaniu przy 29 West 9th Street w Greenwich Village, gdzie pisał i ilustrował Where the Wild Things Are. Później posiadał pied-à-terre przy 40 Fifth Avenue, gdzie pracował i zatrzymywał się okazjonalnie po przeprowadzce na stałe do Ridgefield w stanie Connecticut.

Mówił:

„Tak naprawdę nie wierzę, że dziecko, którym byłem, dorosło i stało się mną. Ono wciąż gdzieś istnieje — w sposób bardzo konkretny, plastyczny, fizyczny. Czuję wobec niego ogromną troskę i zainteresowanie. Staram się z nim nieustannie komunikować. Jednym z moich największych lęków jest utrata tego kontaktu”.

Maurice Sendak czerpał inspirację z ogromnej liczby malarzy, muzyków i pisarzy. Jednym z jego najwcześniejszych i najbardziej osobistych wpływów był ojciec, Philip Sendak. Według Maurice’a ojciec opowiadał historie z Tory, wzbogacając je jednak o pikantne szczegóły. Nie zdając sobie sprawy, że są one nieodpowiednie dla dzieci, młody Maurice był często odsyłany ze szkoły do domu po powtarzaniu ojcowskich „miękkopornograficznych historii biblijnych”. Gregory Maguire pisał, że Sendak „czuł się spokrewniony z takimi postaciami jak Emily Dickinson, Keats, Henry James i Homer”. Margalit Fox zauważyła:

„W dużej mierze samouk, pan Sendak był w swojej najlepszej formie jak sztetlowy Blake — ukazujący świetlisty świat, jednocześnie piękny i przerażający, zawieszony pomiędzy jawą a snem. Dzięki temu potrafił oddać zarówno porywczą swobodę, jak i wszechobecną melancholię wewnętrznego życia dzieci. (…) Jego styl wizualny wahał się od misternie kreskowanych scen przypominających XIX-wieczne grafiki, przez lekkie akwarele przywodzące na myśl Chagalla, po odważne, obłe postacie inspirowane komiksami, które kochał przez całe życie — z ogromnymi stopami, ledwie mieszczącymi się na stronie. Często powtarzał, że nigdy nie nauczył się rysować stóp”.

Wśród innych wczesnych wpływów znajdowały się Fantazja Walta Disneya oraz Myszka Miki, stworzona w roku narodzin Sendaka — 1928. Opisywał Mikiego jako źródło radości i szczęścia w dzieciństwie. Mówił: „Moimi bogami są Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson i Mozart. Wierzę w nich całym sercem”. O Dickinson powiedział: „Mam maleńką Emily Dickinson, tak wielką, że noszę ją zawsze w kieszeni. Wystarczy przeczytać trzy jej wiersze. Jest tak odważna. Tak silna. Tak namiętna. Od razu czuję się lepiej”. O Mozarcie stwierdził: „Gdy w moim pokoju gra Mozart, obcuję z czymś, czego nie potrafię wyjaśnić. (…) Jeśli życie ma jakiś sens, to dla mnie było nim usłyszenie Mozarta”.

Maurice Sendak zmarł 8 maja 2012 roku w szpitalu Danbury w Danbury w stanie Connecticut w wieku 83 lat w wyniku powikłań po udarze. Zgodnie z jego wolą ciało zostało skremowane, a prochy rozsypane w nieujawnionym miejscu. Spike Jonze wspominał: „Patrzyłem na te ilustracje — gdy sypialnia Maxa zamienia się w las — i było w nich coś magicznego”. Jonze wyreżyserował filmową adaptację Where the Wild Things Are oraz dokument Tell Them Anything You Want: A Portrait of Maurice Sendak (oba z 2009 roku). Autor R. L. Stine nazwał śmierć Sendaka „smutnym dniem dla literatury dziecięcej i dla świata”. Tom Hanks powiedział: „Maurice Sendak pomógł wychować moje dzieci — wszystkie czworo wielokrotnie słyszały: ‘W noc, gdy Max założył wilczy strój…’”.

Stephen Colbert, który przeprowadził z Sendakiem jeden z jego ostatnich publicznych wywiadów, powiedział: „Wszyscy jesteśmy zaszczyceni, że mogliśmy choć na chwilę zostać zaproszeni do jego świata”. W styczniu 2012 roku, w jednym z odcinków The Colbert Report, Sendak uczył Colberta rysowania i napisał rekomendację do parodystycznej książki dziecięcej Colberta I Am a Pole (And So Can You!), opublikowanej w dniu śmierci Sendaka, z komentarzem: „Smutne jest to, że naprawdę mi się podoba!”.

Sezon 2012 baletu Dziadek do orzechów Pacific Northwest Ballet — ze scenografią i kostiumami zaprojektowanymi przez Sendaka — został poświęcony jego pamięci.

Jego ostatnia książka, Bumble-Ardy, ukazała się osiem miesięcy przed śmiercią. Pośmiertnie wydano książkę obrazkową My Brother’s Book w lutym 2013 roku. Film Spike’a Jonze’a Her został dedykowany pamięci Sendaka oraz Jamesa Gandolfiniego. Richard Robinson ze Scholastic Corporation powiedział: „Maurice Sendak uchwycił dzieciństwo w olśniewających opowieściach i rysunkach, które będą żyły wiecznie”. Gregory Maguire pisał, że Sendak rozumiał, iż „dzieci są w pełni ludźmi — ograniczonymi jedynie brakiem słownictwa i wprawy w opisywaniu swojego życia”.

PORTRAIT with HISTORY Maurice Sendak

Maurice Bernard Sendak (/ˈsɛndæk/; June 10, 1928 – May 8, 2012) was an American author and illustrator of children's books. Born to Polish-Jewish parents, his childhood was impacted by the death of many of his family members during the Holocaust. Sendak illustrated his own books as well as those by other authors, such as the Little Bear series by Else Holmelund Minarik. He achieved acclaim with Where the Wild Things Are (1963), the first of a trilogy followed by In the Night Kitchen (1970) and Outside Over There (1981). He designed sets for operas, notably Mozart's The Magic Flute.

In 1987, Sendak was the subject of an American Masters documentary, "Mon Cher Papa". In 1996, he received the National Medal of Arts. Per Margalit Fox, Sendak, "the most important children's book artist of the 20th century", "wrenched the picture book out of the safe, sanitized world of the nursery and plunged it into the dark, terrifying and hauntingly beautiful recesses of the human psyche."

Sendak was born on June 10, 1928, in Brooklyn, New York, to Polish-Jewish immigrants Sadie (née Schindler) and Philip Sendak, a dressmaker. Maurice said that his childhood was a "terrible situation" due to the death of members of his extended family during the Holocaust which introduced him at a young age to the concept of mortality. His love of books began when, as a child, he developed health issues and was confined to his bed. He was "enthralled by Mickey Mouse (who was created the year of his birth), by American comics, and by the bright lights of Manhattan." When he was 12 years old, he decided to become an illustrator after watching Walt Disney's film Fantasia (1940).

Maurice was the youngest of three siblings, born five years after Jack Sendak and nine years after Natalie Sendak. Jack also became an author of children's books, two of which were illustrated by Maurice in the 1950s. In 2011, Maurice was working on a book about noses, and he attributed his love of the olfactory organ to his brother Jack, who — in Sendak's opinion — had a great nose.

At the New York Art Students League, he took a class from John Groth, who taught him “a sense of the enormous potential for motion, for aliveness in illustration … He himself … showed how much fun creating in it could be.”

Maurice Sendak began his professional career in 1947 with illustrations for a popular science book, Atomics For the Millions. One of Sendak's first professional commissions, when he was 20 years old,was creating window displays for the toy store FAO Schwarz. The store's children's book buyer introduced him to Ursula Nordstrom, children's book editor at Harper & Row, who would go on to edit E. B. White's Charlotte's Web (1952) and Louise Fitzhugh's Harriet the Spy (1964). This led to his first illustrations for a children's book, for Marcel Aymé's The Wonderful Farm (1951). His work appears in eight books by Ruth Krauss, including A Hole is to Dig (1952), which brought wide attention to his artwork. He illustrated the first five books in Else Holmelund Minarik's Little Bear series. The Maurice Sendak Foundation cites Krauss, Nordstrom and Crockett Johnson as mentors to Sendak. He made his solo debut with Kenny's Window (1956). He published the Nutshell Library (1962), consisting of Alligators All Around, One Was Johnny, Pierre and Chicken Soup With Rice. Sendak said of Nordstrom: “She treated me like a hothouse flower, watered me for ten years, and hand-picked the works that were to become my permanent backlist and bread-and-butter support.”

Sendak gained international acclaim after writing and illustrating Where the Wild Things Are (1963), edited by Nordstrom. It features Max, a boy who "rages against his mother for being sent to bed without any supper". The book's depictions of fanged monsters concerned some parents when it was first published, as his characters were somewhat grotesque in appearance. Sendak explained that the title came from the Yiddish phrase vilde chaya, or “wild beast.”: “It’s what almost every Jewish mother or father says to their offspring, ‘You’re acting like a vilde chaya! Stop it!’” It won the Caldecott Medal, considered the highest honor for picture books in the United States. Humphrey Carpenter and Mari Prichard write that "it is generally considered unequaled in its exploration of a child's fantasy world and its relation to real life." It was adapted into an opera by Oliver Knussen and a film by Spike Jonze.

Sendak later recounted the reaction of a fan: A little boy sent me a charming card with a little drawing on it. I loved it. I answer all my children's letters–sometimes very hastily–but this one I lingered over. I sent him a card and I drew a picture of a Wild Thing on it. I wrote, "Dear Jim: I loved your card." Then I got a letter back from his mother and she said: "Jim loved your card so much he ate it." That to me was one of the highest compliments I've ever received. He didn't care that it was an original Maurice Sendak drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it.

Sendak illustrated The Bat Poet (1964), a children's book by Randall Jarrell. When Sendak saw a manuscript of Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories, the first children's book by Isaac Bashevis Singer, on the desk of an editor at Harper & Row, he offered to illustrate it. It was first published in 1966 and received a Newbery Honor. Sendak was enthusiastic about the collaboration. He once wryly remarked that his parents were "finally" impressed by their youngest child when he collaborated with Singer.

Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More To Life (1967), inspired by Sendak's dog, Jennie, was his favorite of his books. He called it “my requiem for [Jennie]—an unsentimental, even comic requiem to a shrewd, stubborn, loyal, and lovable creature whose all consuming passion was food."

In the Night Kitchen (1970) is "a further exploration of a boy's fantasy world, this time closely based on Sendak's childhood memories of New York life." Fox writes "the huge, flat, brightly colored illustrations" are "a tribute to the New York of Mr. Sendak’s childhood, recalling the 1930s films and comic books he adored all his life." Sendak explained: "It was an homage to everything I loved: New York, immigrants, Jews, Laurel and Hardy, Mickey Mouse, King Kong, movies. I just jammed them into one cuckoo book.” It has often been censored for its drawings of a young boy prancing naked through the story. The book has been challenged in several U.S. states including Illinois, New Jersey, Minnesota, and Texas. In the Night Kitchen regularly appears on the American Library Association's list of "frequently challenged and banned books". It was listed number 21 on the "100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–1999".

Outside Over There (1981) the story of a girl named Ida and her sibling jealousy and responsibility. Her father is away, so Ida is left to watch her baby sister, much to her dismay. Her sister is kidnapped by goblins and Ida must go off on a magical adventure to rescue her. At first, she is not really eager to get her sister and nearly passes right by her when she becomes absorbed in the magic of the quest. In the end, she rescues her sister, destroys the goblins, and returns home committed to caring for her sister until her father returns. This rescue story includes an illustration of a ladder leaning out of the window of a home, which according to one report, was based on the crime scene in the Lindbergh kidnapping, "which terrified Sendak as a child." Carpenter and Prichard write, "More dark in subject matter than Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen, it was published on both adult and children's book lists, and showed a marked change in illustrative style, entirely away from the comic-strip manner that was always partly apparent in the other two." Sendak included a cameo from one of his favorite composers, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. A collection of his essays and lectures were published as Caldecott & Co.: Notes on Books and Pictures (1988).

„…Maurice’a Sendaka spotkałem i fotografowałem 1 grudnia 1986 roku w Nowym Jorku, przy okazji ukazania się kolejnego wydania książki The Bee-Man of Orn Franka R. Stocktona, do której ilustracje wykonał Sendak. Muszę powiedzieć, że artysta zrobił na mnie ogromne wrażenie, dlatego zdecydowałem się na realizację dużej serii zdjęć…”— Czesław Czapliński

In 1993, Sendak published We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy, about the AIDS crisis. Later in the 1990s, Sendak approached playwright Tony Kushner to write a new English-language version of the Czech composer Hans Krása's Holocaust opera Brundibár which, remarkably, had been performed by children in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Kushner wrote the text for Sendak's illustrated book of the same name, published in 2003. The book was named one of The New York Times Book Review's 10 Best Illustrated Books of 2003. Gregory Maguire wrote: “In a career that spans 50 years and counting, as Sendak’s does, there are bound to be lesser works. Brundibar is not lesser than anything.”

In 2011, Sendak adapted his Sesame Street short Bumble Ardy into a children's book, his first in over thirty years, and ultimately his last published work before his death. My Brother's Book (2013) was published posthumously. Dwight Garner wrote "Its charms are simmering and reflective ones. This moral fable may find its largest audience among adults."

Sendak was an early member of the National Board of Advisors of the Children's Television Workshop during the development stages of the Sesame Street television series. He created two animated stories for the series: Bumble Ardy, an animated sequence with Jim Henson as the voice of Bumble Ardy, and Seven Monsters. Sendak later adapted Seven Monsters into the book Seven Little Monsters, which itself would be adapted into an animated television series.

Sendak wrote an animated musical, Really Rosie, featuring the voice of Carole King and broadcast in 1975. It is available on video (usually as part of video compilations of his work). An album of the songs was also produced. He contributed the opening segment to Simple Gifts, a Christmas collection of six animated shorts shown on PBS in 1977 and later released on VHS in 1993. He adapted Where the Wild Things Are for the stage in 1979. Additionally, he designed sets and costumes for many operas and ballets, including the award-winning Pacific Northwest Ballet 1983 production of Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker, Glyndebourne Festival Opera's productions of Prokofiev's The Love for Three Oranges (1982), Ravel's L'enfant et les sortilèges and L'heure espagnole (1987) and Knussen's adaptation of Sendak's own Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life (1985), Houston Grand Opera's productions of Mozart's The Magic Flute (1981) and Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel (1997), Los Angeles County Music Center's 1990 production of Mozart's Idomeneo, New York City Opera's production of Janáček's The Cunning Little Vixen (1981) and the Lyric Opera of Kansas City's production of Mozart's The Goose of Cairo (1982).

In 2003, Chicago Opera Theatre produced Sendak and Kushner's adaptation of Brundibár. In 2005, Berkeley Repertory Theatre, in collaboration with Yale Repertory Theatre and Broadway's New Victory Theater, produced a substantially re-worked version of the Sendak-Kushner adaptation. In 2004, Sendak worked with the Shirim Klezmer Orchestra in Boston on their project Pincus and the Pig: A Klezmer Tale. This Klezmer version of Prokofiev's best-known musical story for children, Peter and the Wolf, featured Maurice Sendak as the narrator. He also illustrated the cover art.

Margalit Fox writes that "His art graced the writing of other eminent authors for children and adults, including Hans Christian Andersen, Leo Tolstoy, Herman Melville, William Blake and Isaac Bashevis Singer."

Sendak mentioned in a September 2008 article in The New York Times that he was gay and had lived with his partner, psychoanalyst Eugene David Glynn (February 25, 1926 – May 15, 2007), for 50 years before Glynn's death in May 2007. Revealing that he never told his parents, he said, "All I wanted was to be straight so my parents could be happy. They never, never, never knew." Sendak's relationship with Glynn was referenced by other writers before (including Tony Kushner in 2003) and Glynn's 2007 death notice identified Sendak as his "partner of fifty years". After his partner's death, Sendak donated $1 million to the Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services in memory of Glynn, who treated young people there. The money will go to a clinic which is to be named for Glynn.

Sendak was an atheist. In a 2011 interview, he said that he did not believe in God and explained that he felt that religion, and belief in God, "must have made life much easier [for some religious friends of his]. It's harder for us non-believers."

In the early 1960s, Sendak lived in a basement apartment at 29 West 9th Street in Greenwich Village where he wrote and illustrated Wild Things. Later he had a nearby pied-à-terre at 40 Fifth Avenue where he worked and stayed occasionally after moving full-time to Ridgefield, Connecticut.

He said: "I don't really believe that the kid I was has grown up into me. He still exists somewhere in the most graphic, plastic, physical way for me. I have tremendous concern for, and interest in, him. I try to communicate with him all the time. One of my worst fears is losing contact."

Maurice Sendak drew inspiration and influences from a vast number of painters, musicians, and authors. Going back to his childhood, one of his earliest memorable influences was actually his father, Philip Sendak. According to Maurice, his father related tales from the Torah; however, he would embellish them with racy details. Not realizing that this was inappropriate for children, young Maurice was frequently sent home after retelling his father's "softcore Bible tales" at school. Gregory Maguire says Sendak "felt he was relative to people like Emily Dickinson and Keats and Henry James and Homer." Margalit Fox wrote: "A largely self-taught illustrator, Mr. Sendak was at his finest a shtetl Blake, portraying a luminous world, at once lovely and dreadful, suspended between wakefulness and dreaming. In so doing, he was able to convey both the propulsive abandon and the pervasive melancholy of children’s interior lives. ... His visual style could range from intricately crosshatched scenes that recalled 19th-century prints to airy watercolors reminiscent of Chagall to bold, bulbous figures inspired by the comic books he loved all his life, with outsize feet that the page could scarcely contain. He never did learn to draw feet, he often said."

Sendak had other influences growing up, including Walt Disney's Fantasia and Mickey Mouse. Mickey Mouse was created in the year Sendak was born, 1928, and Sendak described Mickey as being a source of joy and pleasure for him while growing up. He has been quoted as saying, "My gods are Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson, Mozart. I believe in them with all my heart." Of Dickinson, he said: "I have a little tiny Emily Dickinson so big that I carry in my pocket everywhere. And you just read three poems of Emily. She is so brave. She is so strong. She is such a passionate little woman. I feel better." Of Mozart, he said, "When Mozart is playing in my room, I am in conjunction with something I can't explain. ... I don't need to. I know that if there's a purpose for life, it was for me to hear Mozart."

Sendak died at Danbury Hospital in Danbury, Connecticut on May 8, 2012, at age 83, due to complications from a stroke. In accordance with his wishes, his body was cremated and his ashes were scattered at an undisclosed location. Spike Jonze recalled "I would look at those pictures—where Max's bedroom turns into a forest—and there was something that felt like magic there." Jonze directed the film adaptation Where the Wild Things Are and the documentary Tell Them Anything You Want: A Portrait of Maurice Sendak (both 2009). Author R. L. Stine called Sendak's death "a sad day in children's books and for the world." Tom Hanks said "Maurice Sendak helped raise my kids—all four of them heard 'The night Max wore his wolf suit...' many times."

Stephen Colbert, who interviewed Sendak in one of his last public appearances, said of Sendak: "We are all honored to have been briefly invited into his world." On a January 2012 episode of The Colbert Report, Sendak taught Colbert how to illustrate and provided a book blurb for Colbert's spoof children's book, I Am a Pole (And So Can You!) The book was published on the day of Sendak's death with his blurb: "The sad thing is, I like it!"

The 2012 season of Pacific Northwest Ballet's The Nutcracker, for which Sendak designed the set and costumes, was dedicated to his memory.

His final book, Bumble-Ardy, was published eight months before his death. A posthumous picture book, My Brother's Book, was published in February 2013. (2009). Jonze's film Her was dedicated in memory of Sendak and Where the Wild Things Are co-star James Gandolfini. Richard Robinson, executive of Scholastic Corporation, said "Maurice Sendak captured childhood in brilliant stories and drawings that will live forever." Gregory Maguire, author of Making Mischief: A Maurice Sendak Appreciation wrote that Sendak realized "Children are full humans, compromised only by their lack of vocabulary and practice in reporting how they live. But they live as fully as Sendak himself lived right up to his last months and weeks and hours. ... [S]ome more sentimental scrap of me (that he would have scorned) hopes he is settling down to some nice bowl of chicken soup with rice with Emily Dickinson or Herman Melville. Though they have been impatient to meet him in person for a very long time, no doubt they’ll greet him as a fellow king. By now, Sendak is finding his dinner waiting for him. And it is still hot."

Komentarze