PORTRET z HISTORIĄ George Ames Plimpton

- Czesław Czapliński

- 19 sty

- 26 minut(y) czytania

George Ames Plimpton (18 marca 1927 – 25 września 2003) był amerykańskim pisarzem. Znany był ze swojego pisarstwa sportowego oraz ze współzałożenia czasopisma The Paris Review, a także z patrycjuszowskich manier i charakterystycznego akcentu. Zasłynął z uprawiania „dziennikarstwa uczestniczącego”, obejmującego relacje z jego czynnego udziału w profesjonalnych wydarzeniach sportowych, występu w westernie, wykonania numeru komediowego w Caesars Palace w Las Vegas oraz grania z Nowojorską Orkiestrą Filharmoniczną, po czym opisywał te doświadczenia z punktu widzenia amatora.

Według The New York Times jego „wyczyny redaktorskie i pisarskie oscylowały między literaturą piękną a dowcipnymi relacjami z rozmaitych szalonych prób wślizgnięcia się do cudzych, prestiżowych karier… wysoki, elegancki mężczyzna o niewyczerpanej energii i nieustającej pogodzie ducha, w 1953 roku został pierwszym i jedynym redaktorem naczelnym The Paris Review. Wszechobecny na przyjęciach książkowych i innych wystawnych wydarzeniach towarzyskich, niestrudzenie angażował się w promowanie poważnej, współczesnej prozy publikowanej przez to czasopismo… Wszystko to przyczyniało się do uroku lektury opisów często pechowych przygód pana Plimptona jako ‘zawodowego’ sportowca, komika stand-upowego, filmowego czarnego charakteru czy artysty cyrkowego; przygody te utrwalał w dowcipnej, eleganckiej prozie w niemal trzech tuzinach książek”.

Plimpton urodził się w Nowym Jorku 18 marca 1927 roku i spędził tam dzieciństwo, uczęszczając do St. Bernard’s School oraz dorastając w dwupoziomowym apartamencie na Upper East Side Manhattanu, przy 1165 Fifth Avenue. Latem mieszkał w osadzie West Hills w Huntington, w hrabstwie Suffolk na Long Island.

Był synem Francisa T. P. Plimptona oraz wnukiem Frances Taylor Pearsons i George’a Arthura Plimptona. Jego ojciec był odnoszącym sukcesy prawnikiem korporacyjnym i partnerem imiennym kancelarii Debevoise and Plimpton; został mianowany przez prezydenta Johna F. Kennedy’ego zastępcą ambasadora USA przy Organizacji Narodów Zjednoczonych i pełnił tę funkcję w latach 1961–1965.

Jego matką była Pauline Ames, córka botanika Oakesa Amesa (1874–1950) oraz artystki Blanche Ames. Oboje dziadkowie Plimptona ze strony matki nosili nazwisko Ames; jego matka była wnuczką odznaczonego Medalem Honoru Adelberta Amesa (1835–1933), amerykańskiego marynarza, żołnierza i polityka, oraz Olivera Amesa, amerykańskiego polityka i 35. gubernatora stanu Massachusetts (1887–1890). Była również prawnuczką ze strony ojca Oakesa Amesa (1804–1873), przemysłowca i kongresmena zamieszanego w skandal kolejowy Crédit Mobilier z 1872 roku, oraz generała-gubernatora Nowego Orleanu Benjamina Franklina Butlera, amerykańskiego prawnika i polityka, który reprezentował Massachusetts w Izbie Reprezentantów USA, a później pełnił funkcję 33. gubernatora tego stanu.

Syn Plimptona opisywał go jako białego anglosaskiego protestanta (WASP) i pisał, że oboje rodzice Plimptona wywodzili się od pasażerów statku Mayflower.

George miał troje rodzeństwa: Francisa Taylora Pearsonsa Plimptona Jr., Oakesa Amesa Plimptona oraz Sarah Gay Plimpton.

Po ukończeniu St. Bernard’s School Plimpton uczęszczał do Phillips Exeter Academy (z której został wydalony tuż przed ukończeniem nauki) oraz do Daytona Beach High School, gdzie uzyskał dyplom szkoły średniej, zanim w lipcu 1944 roku rozpoczął studia w Harvard College. Pisał dla Harvard Lampoon, był członkiem Hasty Pudding Club, Pi Eta, Signet Society oraz Porcellian Club i studiował filologię angielską. Został przyjęty na Harvard jako członek rocznika 1948, lecz ukończył studia dopiero w 1950 roku z powodu przerwy na służbę wojskową. Był także utalentowanym obserwatorem ptaków.

Studia Plimptona na Harvardzie zostały przerwane przez służbę wojskową w latach 1945–1948, podczas której służył we Włoszech jako kierowca czołgu w armii. Po ukończeniu Harvardu w 1950 roku studiował w King’s College w Cambridge w latach 1950–1952, gdzie uzyskał dyplom z języka angielskiego z trzeciej klasy wyróżnieniem.

W 1952 roku Plimpton został zwerbowany przez Petera Matthiessena do zespołu literackiego czasopisma The Paris Review, założonego przez Matthiessena, Thomasa H. Guinzburga oraz Harolda L. Humesa. Pismo to miało ogromne znaczenie w świecie literatury, choć nigdy nie było finansowo silne; przez pierwsze pół wieku istnienia było podobno w dużej mierze finansowane przez wydawców oraz samego Plimptona. Matthiessen przejął magazyn od Humesa i usunął go ze stanowiska redaktora, zastępując go Plimptonem, wykorzystując przy tym działalność pisma jako przykrywkę dla własnych działań w CIA. Jean Stein została współredaktorką Plimptona. Plimpton był również związany z paryskim pismem literackim Merlin, które upadło po wycofaniu wsparcia przez Departament Stanu USA. Przyszły poeta laureat Donald Hall, który poznał Plimptona jeszcze w Exeter, pełnił funkcję redaktora działu poezji. Jednym z najważniejszych odkryć pisma był pisarz i scenarzysta Terry Southern, który mieszkał wówczas w Paryżu i nawiązał z Plimptonem przyjaźń na całe życie, podobnie jak pisarz Alexander Trocchi oraz przyszły pionier muzyki klasycznej i jazzowej David Amram. W 1958 roku Plimpton opublikował wpływowy artykuł o Vali Myers. W tym samym roku przeprowadził dla The Paris Review wywiad z Ernestem Hemingwayem.

Plimpton zasłynął z udziału w profesjonalnych wydarzeniach sportowych, które następnie opisywał z perspektywy amatora. Jak pisał The New York Times, „jako ‘dziennikarz uczestniczący’ pan Plimpton uważał, że autorom literatury faktu nie wystarcza samo obserwowanie wydarzeń; muszą się w nie zanurzyć, by w pełni zrozumieć ich istotę. Na przykład sądził, że narady futbolowe i rozmowy na ławce rezerwowych stanowią ‘tajny świat, a jeśli jest się podglądaczem, chce się tam być i doświadczać tego bezpośrednio’”. Inspirował się Paulem Gallico, o którym mówił: „To, co zrobił Gallico, polegało na zejściu z loży prasowej”.W 1958 roku, przed posezonowym meczem pokazowym na stadionie Yankee Stadium pomiędzy drużynami prowadzonymi przez Willie’ego Maysa (Liga Narodowa) i Mickeya Mantle’a (Liga Amerykańska), Plimpton wystąpił jako miotacz przeciwko drużynie Ligi Narodowej. Doświadczenie to opisał w książce Out of My League (1961). (Zamierzał zmierzyć się z oboma składami, lecz szybko opadł z sił i został zmieniony przez Ralpha Houka). Plimpton stoczył także trzyrundowy sparing z legendami boksu Archiem Moore’em i Sugar Rayem Robinsonem, realizując zlecenie dla Sports Illustrated. Ernest Hemingway chwalił Out of My League jako dzieło „pięknie zaobserwowane i niezwykle pomysłowe, relację z dobrowolnie podjętej próby, która ma mrożącą krew w żyłach jakość prawdziwego koszmaru… To ciemna strona księżyca Waltera Mitty’ego”.

W 1963 roku Plimpton wziął udział w przedsezonowych przygotowaniach drużyny Detroit Lions z National Football League jako rezerwowy rozgrywający i rozegrał kilka akcji w wewnętrznym meczu treningowym. Wydarzenia te opisał w swojej najsłynniejszej książce Paper Lion (1966), na podstawie której w 1968 roku powstał film z Alanem Aldą w roli głównej. Plimpton powrócił do futbolu zawodowego w 1971 roku, tym razem dołączając do obrońców tytułu mistrza Super Bowl – Baltimore Colts – i wystąpił w meczu pokazowym przeciwko swojej dawnej drużynie, Lions. Doświadczenia te stały się podstawą książki Mad Ducks and Bears (1973), choć znaczna jej część dotyczyła pozaboiskowych przygód i obserwacji związanych z przyjaciółmi futbolistami: Alexem Karrasem („Mad Duck”) i Johnem Gordym („Bear”).

Książka Plimptona The Bogey Man (1968) opisuje jego próbę gry w zawodowym golfie w cyklu PGA Tour w epoce Nicklausa i Palmera w latach 60. XX wieku. W ramach innych wyzwań dla Sports Illustrated próbował gry w brydża na najwyższym poziomie oraz przez pewien czas występował jako akrobata chodzący po linie w cyrku. Niektóre z tych doświadczeń, takie jak jego pobyt w Colts czy próba kariery jako komik stand-upowy, zostały zaprezentowane w telewizji ABC w formie serii programów specjalnych. W książce Open Net (1985) trenował jako bramkarz hokejowy z drużyną Boston Bruins, a nawet wystąpił w części przedsezonowego meczu National Hockey League.

Wśród innych przygód próbował „akrobacji jako artysta powietrzny w cyrku Clyde Beatty–Cole Brothers — ponosząc sromotną porażkę”. Z większym powodzeniem spróbował natomiast „swoich sił jako perkusista w Nowojorskiej Orkiestrze Filharmonicznej (gdzie nietrafione uderzenie w gong przyniosło mu natychmiastowe brawa dyrygenta Leonarda Bernsteina)”.

W numerze Sports Illustrated z 1 kwietnia 1985 roku Plimpton przeprowadził szeroko komentowany primaaprilisowy żart. Przy pomocy organizacji New York Mets oraz kilku jej zawodników napisał relację o nieznanym miotaczu z obozu wiosennego Mets, Siddharcie Finchu, który rzekomo rzucał piłkę z prędkością ponad 160 mil na godzinę, nosił na jednej nodze but trekkingowy i był praktykującym buddystą studiującym jogę w Tybecie. Artykuł zawierał wiele wskazówek, że historia jest żartem, począwszy od podtytułu: „Jest miotaczem, częściowo joginem i częściowo pustelnikiem. Imponująco wyzwolony z naszego wystawnego stylu życia, Sidd zastanawia się nad jogą — i swoją przyszłością w baseballu”. Był to akrostych odczytywany jako „Happy April Fools’ Day — a(h) fib”. Tekst był jednak tak przekonujący, że wielu czytelników w niego uwierzyło, a popularność żartu skłoniła Plimptona do rozwinięcia historii w książce The Curious Case of Sidd Finch (1987).

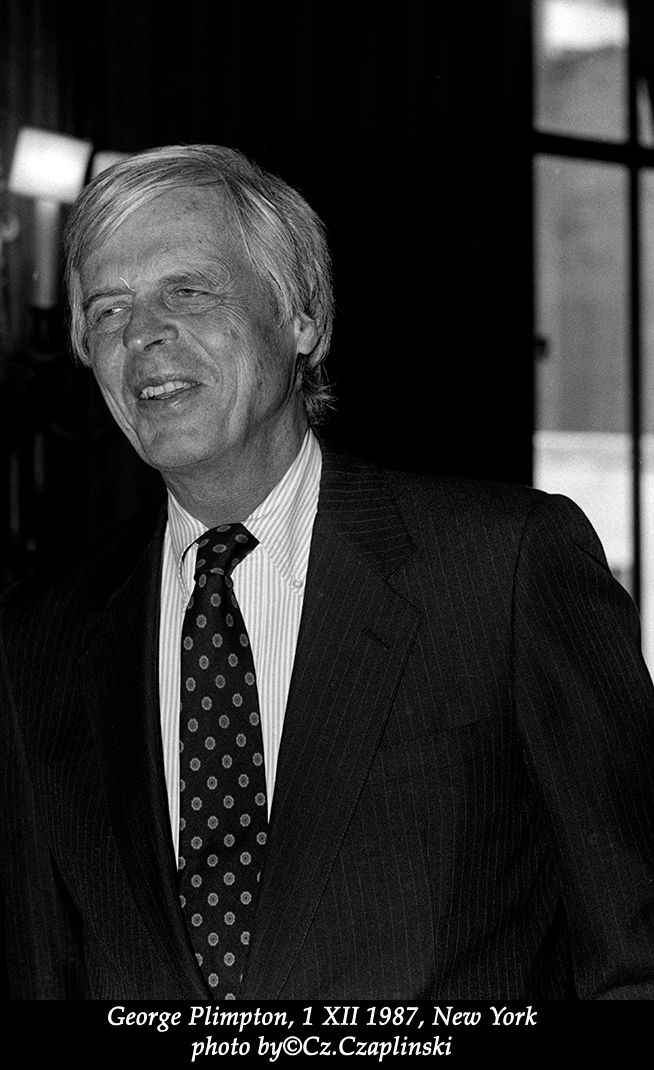

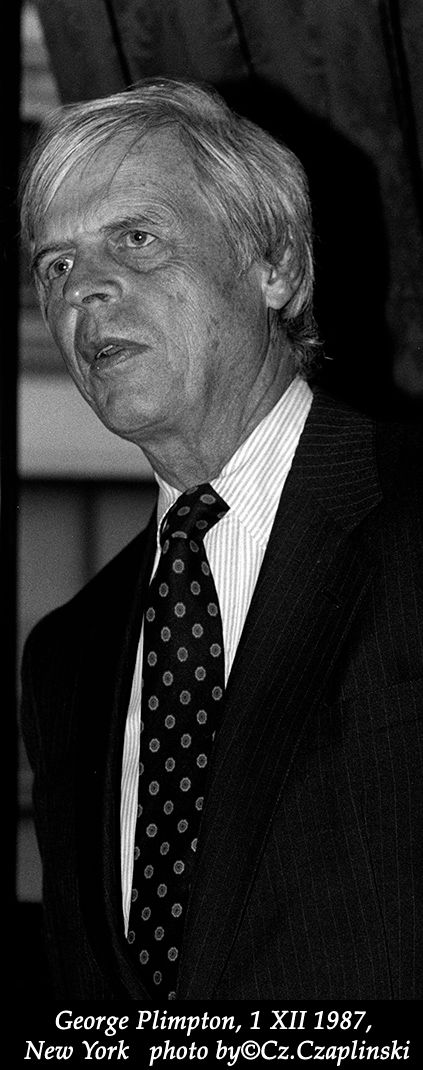

„…George Plimptona, jak zresztą wiele wybitnych osób, poznałem dzięki mojemu przyjacielowi, prezesowi Amerykańskiego PEN Clubu Jerzemu Kosińskiemu. 1 grudnia 1987 r. spotkaliśmy się w Nowym Jorku, muszę powiedzieć, że było to niezwykłe spotkanie, podczas którego zrobiłem serię unikalnych zdjęć, które potem przekazałem Kosińskiemu i Plimptonowi…” – Czesław Czapliński.

Plimpton był specjalistą od materiałów wybuchowych w armii amerykańskiej w okresie powojennym, po II wojnie światowej. Po powrocie do Nowego Jorku z Paryża regularnie odpalał fajerwerki podczas wieczornych przyjęć. Jego fascynacja sztucznymi ogniami rozwijała się coraz bardziej i w 1975 roku, w Bellport na Long Island, we współpracy z firmą Fireworks by Grucci, podjął próbę pobicia rekordu świata na największy fajerwerk. Jego wyrób pirotechniczny — rzymska świeca nazwana „Fat Man” — ważył 720 funtów (330 kg) i miał wznieść się na wysokość 1000 stóp (300 m) lub więcej, tworząc szeroką gwiaździstą eksplozję.

Po odpaleniu fajerwerk pozostał jednak na ziemi i eksplodował, tworząc krater o szerokości 35 stóp (11 m) i głębokości 10 stóp (3 m). Kolejna próba, przeprowadzona na przylądku Cape Canaveral, spowodowała wzniesienie się ładunku na około 50 stóp (15 m), a eksplozja wybiła 700 okien w Titusville na Florydzie. Wraz z Felixem Gruccim Plimpton wziął udział w 16. Międzynarodowym Festiwalu Fajerwerków w Monte Carlo w 1979 roku. Po licznych problemach z transportem i przygotowaniem pokazów Plimpton i Grucci zostali pierwszymi uczestnikami ze Stanów Zjednoczonych, którzy wygrali ten konkurs. Plimpton został mianowany przez burmistrza Johna Lindsaya komisarzem ds. fajerwerków miasta Nowy Jork — nieoficjalne stanowisko, które pełnił aż do śmierci. Wraz z rodziną Gruccich współtworzył choreografię pokazów pirotechnicznych z okazji stulecia Mostu Brooklińskiego w 1983 roku oraz podczas drugiej inauguracji prezydenta Ronalda Reagana. Jego pasja do pirotechniki zaowocowała książką Fireworks (1984), a także programem wideo dla A&E Home Video poświęconym temu tematowi, prezentującym liczne pirotechniczne przygody Plimptona z rodziną Grucci.

Plimpton wspólnie z Jean Stein opracował biografię mówioną Edie Sedgwick pt. Edie: An American Biography (1982). Wystąpił w krótkim materiale filmowym o Sedgwick dołączonym do wydania DVD Ciao! Manhattan. Pojawił się także w dokumencie American Masters stacji PBS poświęconym Andy’emu Warholowi oraz w napisach końcowych filmu Factory Girl z 2006 roku. W 1998 roku opublikował biografię mówioną Trumana Capote’a. W latach 2000–2003 napisał libretto do opery Animal Tales, zamówionej przez Family Opera Initiative, z muzyką Kitty Brazelton i w reżyserii Grethe Barrett Holby. Pisał: „Przypuszczam, że w łagodnej formie jest tu pewna lekcja dla młodych — lub młodych duchem — odwaga, by wyjść i spróbować rozwinąć skrzydła”. W 2002 roku Plimpton współpracował z Terrym Quinnem nad sztuką Zelda, Scott and Ernest, opartą na korespondencji F. Scotta Fitzgeralda, Zeldy Fitzgerald i Ernesta Hemingwaya.

W 1989 roku Plimpton wystąpił w filmie dokumentalnym The Tightrope Dancer, poświęconym życiu i twórczości artystki Vali Myers. W 1994 roku pojawił się w serialu dokumentalnym Kena Burnsa Baseball, dzieląc się osobistymi doświadczeniami związanymi z baseballem oraz komentując pamiętne wydarzenia z historii tej dyscypliny. W 1996 roku wystąpił w filmie dokumentalnym When We Were Kings, opowiadającym o legendarnym pojedynku „Rumble in the Jungle” — walce mistrzowskiej Ali–Foreman z 1974 roku. Plimpton uważał Muhammada Alego za poetę, który ułożył najkrótszy wiersz świata: „Ja? Fiuu!!”.

Plimpton wystąpił w ponad trzydziestu filmach jako statysta lub w epizodycznych rolach. Zagrał Beduina w Lawrence of Arabia (1961), złodzieja w Rio Lobo (1970), antagonistycznego ojca postaci granej przez Toma Hanksa w Volunteers(1985) oraz psychologa w Buntowniku z wyboru (Good Will Hunting, 1997). Sam określał się mianem „Księcia epizodów”. Występował również w reklamach telewizyjnych na początku lat 80., w tym w zapamiętanej kampanii konsoli Intellivision firmy Mattel, w której zachwalał wyższość grafiki i dźwięku gier Intellivision nad Atari 2600.

Był gospodarzem Mouseterpiece Theater, parodii Masterpiece Theatre prezentującej krótkometrażowe animacje Disneya. Miał powracającą rolę dziadka doktora Cartera w serialu Ostry dyżur (ER) oraz był członkiem obsady serialu Nero Wolfe(2001–2002). W odcinku Simpsonów pt. „I'm Spelling as Fast as I Can” prowadzi „Spellympics” i próbuje przekupić Lisę, by przegrała, oferując jej stypendium w jednej z uczelni Seven Sisters oraz kuchenkę elektryczną („idealna do zupy!”).

Karykatura opublikowana 6 listopada 1971 roku w The New Yorker autorstwa Whitney’ego Darrowa Jr. przedstawia sprzątaczkę na kolanach szorującą podłogę w biurze, która mówi do drugiej: „Chciałabym kiedyś zobaczyć, jak George Plimpton robi coś takiego”. W innym rysunku z The New Yorker pacjent spogląda na zamaskowanego chirurga gotowego do operacji i pyta: „Chwileczkę! Skąd mam wiedzieć, że nie jesteś George’em Plimptonem?”. Artykuł w magazynie Madzatytułowany „Some Really Dangerous Jobs for George Plimpton” przedstawiał go m.in. próbującego przepłynąć jezioro Erie, spacerującego nocą po nowojorskim Times Square oraz spędzającego tydzień z Jerrym Lewisem.

Plimpton był znany ze swojego charakterystycznego akcentu, który — jak sam przyznawał — często brano za brytyjski. Opisywał go jako „kosmopolityczny akcent Nowej Anglii” lub „kosmopolityczny akcent wschodniego wybrzeża”. Jego syn Taylor określał go jako mieszankę „starej Nowej Anglii, starego Nowego Jorku, z domieszką akademickiej angielszczyzny King’s College”.

Plimpton był dwukrotnie żonaty. Jego pierwszą żoną, którą poślubił w 1968 roku i z którą rozwiódł się w 1988 roku, była Freddy Medora Espy, asystentka fotografa. Była ona córką pisarzy Willarda R. Espy’ego i Hildy S. Cole, która we wcześniejszym okresie kariery pracowała jako agentka prasowa Kate Smith i Freda Waringa. Mieli dwoje dzieci: Medorę Ames Plimpton oraz Taylora Amesa Plimptona, autora wspomnień Notes from the Night: A Life After Dark.

W 1992 roku Plimpton poślubił Sarah Whitehead Dudley, absolwentkę Uniwersytetu Columbia i niezależną pisarkę. Była ona córką Jamesa Chittendena Dudleya, partnera zarządzającego nowojorskiej firmy inwestycyjnej Dudley & Company, oraz geolożki Elisabeth Claypool. Rodzina Dudleyów założyła 36-akrowe (15 ha) arboretum Highstead w Redding w stanie Connecticut. Plimpton i Dudley byli rodzicami bliźniaczek: Laury Dudley Plimpton oraz Olivii Hartley Plimpton.

Podczas studiów na Harvardzie Plimpton był kolegą z roku i bliskim przyjacielem Roberta F. Kennedy’ego. Plimpton, wraz z byłym dziesięcioboistą Raferem Johnsonem i gwiazdą futbolu amerykańskiego Roseyem Grierem, brał udział w obezwładnieniu Sirhana Sirhana, gdy ten dokonał zamachu na Kennedy’ego po jego zwycięstwie w prawyborach Partii Demokratycznej w Kalifornii w 1968 roku, w dawnym hotelu Ambassador w Los Angeles. Kennedy zmarł następnego dnia w szpitalu Good Samaritan.

Plimpton zmarł 25 września 2003 roku w swoim nowojorskim mieszkaniu na skutek zawału serca, który — jak później ustalono — został wywołany gwałtownym wyrzutem katecholamin. Miał 76 lat.

Coroczne „Amatorskie Mistrzostwa Backgammona”, organizowane w Las Vegas od 1978 roku, nosiły nazwę Pucharu Plimptona.

Plimpton został odznaczony tytułem oficera francuskiego Orderu Sztuki i Literatury (Ordre des Arts et des Lettres) oraz kawalera Legii Honorowej, a także był członkiem Amerykańskiej Akademii Sztuk i Literatury.

Biografia mówiona George, Being George, zredagowana przez Nelsona W. Aldricha Jr., została wydana 21 października 2008 roku. Książka zawiera wspomnienia o Plimptonie autorstwa m.in. Normana Mailera, Williama Styrona, Gaya Talese’a i Gore’a Vidala i powstała przy współpracy zarówno jego byłej żony, jak i wdowy.

Plimpton był bohaterem filmu dokumentalnego American Masters pt. Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself. W filmie pisarz James Salter powiedział o Plimptonie, że „tworzył w gatunku, który naprawdę nie pozwala na wielkość”. Film wykorzystał archiwalne nagrania audio i wideo z wykładów i lektur Plimptona, tworząc narrację pośmiertną.

W 2006 roku muzyk Jonathan Coulton napisał piosenkę zatytułowaną A Talk with George, będącą częścią jego serii „Thing a Week”, jako hołd dla licznych przygód Plimptona i jego podejścia do życia.

Plimpton jest również bohaterem półfikcyjnej gry George Plimpton's Video Falconry z 1983 roku na konsolę ColecoVision, wymyślonej przez humorystę Johna Hodgmana i odtworzonej przez twórcę gier wideo Toma Fulpa.

Badacz i pisarz Samuel Arbesman złożył wniosek do NASA o nadanie imienia Plimptona asteroidzie; NASA wydała certyfikat 7932 Plimpton w 2009 roku. Jego ostatni wywiad ukazał się 2 października 2003 roku w The New York Sports Express, przeprowadzony przez dziennikarza Dave’a Hollandera.

Wybrane publikacje Plimptona: –Letters in Training (listy z Włoch do domu, prywatne wydanie, 1946); –The Rabbit's Umbrella (książka dla dzieci, 1955); –Out of My League (baseball, 1961);–Go Caroline (o Caroline Kennedy, prywatne wydanie, 1963); –Paper Lion (o jego doświadczeniu gry w profesjonalnym futbolu z Detroit Lions, 1966); –The Bogey Man (o podróżach z PGA Tour, 1967); –Mad Ducks and Bears (o zawodnikach Detroit Lions, 1973); –One for the Record: The Inside Story of Hank Aaron's Chase for the Home Run Record (1974); –Shadow Box (boks, m.in. walka z Archie Moore’em i pojedynek Ali-Foreman w Zairze, 1977); –One More July (ostatni obóz treningowy NFL Billa Curry’ego, 1977); –Fireworks: A History and Celebration (1984); –Open Net (hokej na lodzie z Boston Bruins, 1985); –The Curious Case of Sidd Finch (powieść rozszerzająca primaaprilisowy artykuł z Sports Illustrated, 1987); –The X Factor: A Quest for Excellence (1990); –The Best of Plimpton (1990); –Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career(1997); –The Man in the Flying Lawn Chair: And Other Excursions and Observations (2004).

Redaktor: Writers at Work (wywiady z The Paris Review), kilka tomów; American Journey: the Times of Robert Kennedy(z Jean Stein); As Told at the Explorers Club: More Than Fifty Gripping Tales of Adventure; Edie: An American Girl.

Wprowadzenia: The Writer's Chapbook: A Compendium of Fact, Opinion, Wit, and Advice from the 20th Century's Preeminent Writers; Above New York Roberta Camerona.

Wybrane występy filmowe: –Lawrence of Arabia (1962) – Beduin (rola nieuznana); –Beyond the Law (1968) – burmistrz Hickory Hill; –The Detective (1968) – reporter (rola nieuznana); –Paper Lion (1968) – Plimpton jako postać główna, w filmie epizodyczna scena z jego udziałem; –Rio Lobo (1970) – czwarty rewolwerowiec; –The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977) – Quentin Reynolds; –If Ever I See You Again (1978) – Lawrence; –Reds (1981) – Horace Whigham; –Garbo Talks (1984) – on sam (rola nieuznana); –Volunteers (1985) – Lawrence Bourne Jr.; –A Fool and His Money (1989) – Bóg; –Easy Wheels (1989) – chirurg; –The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) – uczestnik imprezy; –L.A. Story (1991) – pogodynk; –Little Man Tate (1991) – Winston F. Buckner; –Ken Burns' Baseball (1994) – on sam (głos); –Just Cause (1995) – Elder Phillips; –Nixon (1995) – prawnik prezydenta; –When We Were Kings (1996) – on sam; –Good Will Hunting (1997) – Henry Lipkin, psychology; –The Last Days of Disco (1998) – klubowicz; –EDtv (1999) – panelista; –Just Visiting (2001) – Dr. Brady; –Sam the Man (2001) – on sam; –The Sports Pages (2001) – on sam; –The Devil and Daniel Webster (2003) – on sam (rola nieuznana); –Factory Girl (2006) – on sam; – Soul Power (2008) – on sam; –Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself (2012) – on sam.

Wybrane występy telewizyjne: –Plimpton! The Man on the Flying Trapeze (1971) – on sam, dokument ABC; –Mouseterpiece Theater (1983–1984) – gospodarz / on sam, Disney Channel; –Uncensored Channels: TV Around the World with George Plimpton (1986); –The Equalizer (1989) – Clinton Brandauer, odcinek „Starfire”; –The Civil War (1990) – George Templeton Strong (głos); –Wings (1994) – Dr. Grayson, odcinek „The Shrink”; –Baseball: A Film by Ken Burns (1994) – on sam (głos); –Married... with Children (1995) – odcinek specjalny „Best O’ Bundy”, on sam; –ER (1998, 2001) – John Truman Carter Sr.; –Saturday Night Live (1999, 2002) – on sam (rola nieuznana); –Just Shoot Me (2000) – on sam; –A Nero Wolfe Mystery (2001–2002) – różne role; –The Simpsons (2003) – on sam, odcinek „I'm Spelling as Fast as I Can”.

Reklamy telewizyjne: –Oldsmobile Vista Cruiser (1968/1969) – Plimpton jako prezenter;

–Intellivision (1980) – kampania reklamowa konsoli Mattel; –„Pop-Secret” – Plimpton jako prezenter.

Charakter literacki: –Plimpton występuje jako postać w powieści Philipa Rotha Exit Ghost.

PORTRAIT with HISTORY George Ames Plimpton

George Ames Plimpton (March 18, 1927 – September 25, 2003) was an American writer. He is known for his sports writing and for helping to found The Paris Review, as well as his patrician demeanor and accent. He was known for "participatory journalism," including accounts of his active involvement in professional sporting events, acting in a Western, performing a comedy act at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, and playing with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and then recording the experience from the point of view of an amateur.

According to The New York Times, his "exploits in editing and writing seesawed between belles lettres and the witty accounts he wrote of his various madcap attempts to slip into other people's high-profile careers ... a lanky, urbane man possessed of boundless energy and perpetual bonhomie, became, in 1953, the first and only editor of The Paris Review. A ubiquitous presence at book parties and other gala social events, he was tireless in his commitment to the serious, contemporary fiction the magazine publishes ... All of this contributed to the charm of reading about Mr. Plimpton's frequently hapless adventures as 'professional' athlete, stand-up comedian, movie bad guy or circus performer; which he chronicled in witty, elegant prose in nearly three dozen books."

Plimpton was born in New York City on March 18, 1927, and spent his childhood there, attending St. Bernard's School and growing up in an apartment duplex on Manhattan's Upper East Side located at 1165 Fifth Avenue. During the summers, he lived in the hamlet of West Hills, Huntington, Suffolk County on Long Island.

He was the son of Francis T. P. Plimpton and the grandson of Frances Taylor Pearsons and George Arthur Plimpton. His father was a successful corporate lawyer and name partner of the law firm Debevoise and Plimpton; he was appointed by President John F. Kennedy as U.S. deputy ambassador to the United Nations, serving from 1961 to 1965.

His mother was Pauline Ames, the daughter of botanist Oakes Ames (1874–1950) and artist Blanche Ames. Both of Plimpton's maternal grandparents were born with the surname Ames; his mother was the granddaughter of Medal of Honor recipient Adelbert Ames (1835–1933), an American sailor, soldier, and politician, and Oliver Ames, a US political figure and the 35th Governor of Massachusetts (1887–1890). She was also the great-granddaughter on her father's side of Oakes Ames (1804–1873), an industrialist and congressman who was implicated in the Crédit Mobilier railroad scandal of 1872; and Governor-General of New Orleans Benjamin Franklin Butler, an American lawyer and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States House of Representatives and later served as the 33rd Governor of Massachusetts.

Plimpton's son described him as a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant and wrote that both of Plimpton's parents were descended from Mayflower passengers.

George had three siblings: Francis Taylor Pearsons Plimpton Jr., Oakes Ames Plimpton, and Sarah Gay Plimpton.

After St. Bernard's School, Plimpton attended Phillips Exeter Academy (from which he was expelled just shy of graduation), and Daytona Beach High School, where he received his high school diploma, before entering Harvard College in July 1944. He wrote for the Harvard Lampoon, was a member of the Hasty Pudding Club, Pi Eta, the Signet Society, and the Porcellian Club and majored in English. Plimpton entered Harvard as a member of the Class of 1948, but did not graduate until 1950 due to intervening military service. He was also an accomplished birdwatcher.

Plimpton's studies at Harvard were interrupted by military service from 1945 to 1948, during which time he served in Italy as an Army tank driver. After finishing at Harvard in 1950, he attended King's College, Cambridge, from 1950 to 1952, and graduated with third class honors in English.

The Paris Review In 1952, Plimpton was recruited by Peter Matthiessen to join the literary journal The Paris Review, founded by Matthiessen, Thomas H. Guinzburg, and Harold L. Humes. This periodical has carried great weight in the literary world, but has never been financially strong; for its first half-century, it was allegedly largely financed by its publishers and by Plimpton. Matthiessen took the magazine over from Humes and ousted him as editor, replacing him with Plimpton, using it as his cover for Matthiessen's CIA activities. Jean Stein became Plimpton's co-editor. Plimpton was associated with the Paris literary magazine Merlin, which folded because the State Department withdrew its support. Future Poet Laureate Donald Hall, who had met Plimpton at Exeter, was Poetry Editor. One of the magazine's most notable discoveries was author and screenwriter Terry Southern, who was living in Paris at the time and formed a lifelong friendship with Plimpton, along with writer Alexander Trocchi and future classical and jazz pioneer David Amram. In 1958, he published an influential article about Vali Myers. That same year, Plimpton interviewed Ernest Hemingway for the Review.

Plimpton was famous for competing in professional sporting events and then recording the experience from the point of view of an amateur. Per The New York Times, "As a 'participatory journalist,' Mr. Plimpton believed that it was not enough for writers of nonfiction to simply observe; they needed to immerse themselves in whatever they were covering to understand fully what was involved. For example, he believed that football huddles and conversations on the bench constituted a 'secret world, and if you're a voyeur, you want to be down there, getting it firsthand'. He was influenced by Paul Gallico, about whom he said: "What Gallico did was to climb down out of the press box." In 1958, prior to a post-season exhibition game at Yankee Stadium between teams managed by Willie Mays (National League) and Mickey Mantle (American League), Plimpton pitched against the National League. This experience was captured in Out of My League (1961). (He intended to face both line-ups, but tired badly and was relieved by Ralph Houk.) Plimpton sparred for three rounds with boxing greats Archie Moore and Sugar Ray Robinson while on assignment for Sports Illustrated. Hemingway praised Out of My League as "beautifully observed and incredibly conceived, his account of a self-imposed ordeal that has the chilling quality of a true nightmare ... It is the dark side of the moon of Walter Mitty."

In 1963, Plimpton attended preseason training with the Detroit Lions of the National Football League as a backup quarterback, and he ran a few plays in an intrasquad scrimmage. These events were recalled in his best-known book, Paper Lion (1966), which was adapted as a 1968 film starring Alan Alda. Plimpton revisited pro football in 1971, this time joining the defending Super Bowl champion Baltimore Colts and seeing action in an exhibition game against his previous team, the Lions. These experiences served as the basis of Mad Ducks and Bears (1973), although much of the book dealt with the off-field escapades and observations of football friends Alex Karras ("Mad Duck") and John Gordy ("Bear").

Plimpton's The Bogey Man (1968) chronicles his attempt to play professional golf on the PGA Tour during the Nicklaus and Palmer era of the 1960s. Among other challenges for Sports Illustrated, he attempted to play top-level bridge, and spent some time as a high-wire circus performer. Some of these events, such as his stint with the Colts, and an attempt at stand-up comedy, were presented on the ABC television network as a series of specials. Open Net (1985) saw him train as an ice hockey goalie with the Boston Bruins, even playing part of a National Hockey League preseason game.

Among other adventures, he attempted "acrobatics as an aerialist for the Clyde Beatty-Cole Brothers Circus—he failed miserably". More happily, he tried "his hand as a percussionist with the New York Philharmonic (where a miss-hit on the gong earned him the immediate applause of conductor Leonard Bernstein)."

In the April 1, 1985, issue of Sports Illustrated, Plimpton pulled off a widely reported April Fools' Day prank. With the help of the New York Mets organization and several Mets players, Plimpton wrote an account of an unknown pitcher in the Mets spring training camp, Siddhartha Finch, who threw a baseball over 160 mph, wore a hiking boot on one foot, and was a practicing Buddhist who had studied yoga in Tibet. The article had many clues that the story was a prank, starting with the subheading: "He's a pitcher, part yogi and part recluse. Impressively liberated from our opulent life-style, Sidd's deciding about yoga—and his future in baseball." This is an acrostic reading "Happy April Fools' Day—a(h) fib". The article was so convincing that many readers believed it, and the popularity of the prank led to Plimpton expanding on Sidd's story in The Curious Case of Sidd Finch (1987).

“…I came to know George Plimpton, as with many other outstanding figures, through my friend, the president of the American PEN Club, Jerzy Kosiński. On December 1, 1987, we met in New York, and I must say it was an extraordinary meeting, during which I took a series of unique photographs that I later gave to Kosiński and Plimpton…” — Czesław Czapliński.

Plimpton was a demolitions expert in the post–World War II Army. After returning to New York from Paris, he routinely launched fireworks at his evening parties. His fireworks fascination flourished, and in 1975, in Bellport, Long Island, with Fireworks by Grucci, he attempted to break the record for the world's largest firework. His firework, a Roman candle named "Fat Man", weighed 720 pounds (330 kg) and was expected to rise to 1,000 feet (300 m) or more and deliver a wide starburst.

When lit, the firework remained on the ground and exploded, blasting a crater 35 feet (11 m) wide and 10 feet (3.0 m) deep. A later attempt, fired at Cape Canaveral, rose approximately 50 feet (15 m) into the air and broke 700 windows in Titusville, Florida. With Felix Grucci, Plimpton competed in the 16th International Fireworks Festival in 1979 in Monte Carlo. After several problems with transporting and preparing the fireworks, Plimpton and Grucci became the first competitors from the United States to win the event. Plimpton was appointed Fireworks Commissioner of New York by Mayor John Lindsay, an unofficial post he held until his death. With the Grucci family, he helped choreograph the fireworks for the 1983 Brooklyn Bridge Centennial Celebration and for the second inauguration of Ronald Reagan. Plimpton's passion for pyrotechnics led him to write Fireworks (1984), and he hosted an A&E Home Video on the subject, featuring his many fireworks adventures with the Gruccis.

Plimpton and Jean Stein edited an oral biography of Edie Sedgwick, Edie: An American Biography (1982). He appeared in a featurette about Sedgwick found on the Ciao! Manhattan DVD. He appeared in the PBS American Masters documentary on Andy Warhol and in the closing credits of the 2006 film Factory Girl. In 1998, Plimpton published an oral biography of Truman Capote. Between 2000 and 2003, he wrote the libretto to the opera Animal Tales, commissioned by Family Opera Initiative, with music by Kitty Brazelton and directed by Grethe Barrett Holby. He wrote, "I suppose in a mild way there is a lesson to be learned for the young, or the young at heart – the gumption to get out and try one's wings". In 2002, Plimpton collaborated with Terry Quinn on Zelda, Scott and Ernest, a play based on the correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Zelda Fitzgerald and Hemingway.

In 1989, Plimpton appeared in the documentary The Tightrope Dancer, about the life and the work of the artist Vali Myers. In 1994, Plimpton appeared in the Ken Burns series Baseball, sharing personal baseball experiences and commenting on memorable events from the history of the game. In 1996, he appeared in the documentary When We Were Kings, about the "Rumble in the Jungle", the 1974 Ali-Foreman Championship fight. Plimpton credited Muhammad Ali as a poet who composed the world's shortest poem: "Me? Whee!!"

Plimpton appeared in more than thirty films as an extra or in cameo appearances. He was a Bedouin in Lawrence of Arabia (1961), a thief in Rio Lobo (1970), Tom Hanks's antagonistic father in Volunteers (1985) and a psychologist in Good Will Hunting (1997). Plimpton called himself "the Prince of Cameos." He also appeared in television commercials in the early 1980s, including a memorable campaign for Mattel's Intellivision. In this campaign, Plimpton touted the superiority regarding the graphics and sounds of Intellivision video games over the Atari 2600.

He hosted Mouseterpiece Theater, a Masterpiece Theatre spoof featuring Disney cartoon shorts. He had a recurring role as the grandfather of Dr. Carter on ER and was a cast member of Nero Wolfe (2001–02). In The Simpsons episode "I'm Spelling as Fast as I Can", he hosts the "Spellympics" and attempts to bribe Lisa to lose with the offer of a scholarship at a Seven Sisters College and a hot plate: "it's perfect for soup!"

A November 6, 1971, cartoon in The New Yorker by Whitney Darrow Jr. shows a cleaning lady on her hands and knees scrubbing an office floor while saying to another one: "I'd like to see George Plimpton do this sometime." In another cartoon in The New Yorker, a patient looks up at the masked surgeon about to operate on him and asks, "Wait a minute! How do I know you're not George Plimpton?" A feature in Mad titled "Some Really Dangerous Jobs for George Plimpton" spotlighted him trying to swim across Lake Erie, strolling through New York's Times Square in the middle of the night, and spending a week with Jerry Lewis.

limpton with Herb Caen and Ann Miller in 1993 Plimpton was known for his distinctive accent which, by Plimpton's own admission, was often mistaken for an English accent. Plimpton himself described it as a "New England cosmopolitan accent" or "Eastern seaboard cosmopolitan" accent. His son, Taylor, described it as a mixture of "old New England, old New York, tinged with a hint of King's College King's English."

Plimpton was married twice. His first wife, whom he married in 1968 and divorced in 1988, was Freddy Medora Espy, a photographer's assistant. She was the daughter of writers Willard R. Espy and Hilda S. Cole, who had, earlier in her career, been a publicity agent for Kate Smith and Fred Waring. They had two children: Medora Ames Plimpton and Taylor Ames Plimpton, who has published a memoir entitled Notes from the Night: A Life After Dark.

In 1992, Plimpton married Sarah Whitehead Dudley, a graduate of Columbia University and a freelance writer. She is the daughter of James Chittenden Dudley, a managing partner of Manhattan-based investment firm Dudley and Company, and geologist Elisabeth

Claypool. The Dudleys established the 36-acre (15 ha) Highstead Arboretum in Redding, Connecticut. Plimpton and Dudley were the parents of twin daughters Laura Dudley Plimpton and Olivia Hartley Plimpton.

At Harvard, Plimpton was a classmate and close personal friend of Robert F. Kennedy. Plimpton, along with former decathlete Rafer Johnson and American football star Rosey Grier, was credited with helping wrestle Sirhan Sirhan to the floor when Kennedy was assassinated following his victory in the 1968 California Democratic primary at the former Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California. Kennedy died the next day at Good Samaritan Hospital.

Plimpton died on September 25, 2003, in his New York City apartment from a heart attack later determined to have been caused by a catecholamine surge. He was 76.

The annual "Amateur Backgammon championships" held in Las Vegas from 1978 onwards were called the Plimpton Cup.

Plimpton was made an officier of the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and a chevalier of the Legion of Honour, and was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

An oral biography, George, Being George was edited by Nelson W. Aldrich Jr., and released on October 21, 2008. The book offers memories of Plimpton from Norman Mailer, William Styron, Gay Talese and Gore Vidal among other writers, and was written with the cooperation of both his ex-wife and his widow.

Plimpton was the subject of the American Masters documentary Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself. In it the writer James Salter said of Plimpton that "he was writing in a genre that really doesn't permit greatness." The film used archival audio and video of Plimpton lecturing and reading to create a posthumous narration.

In 2006, the musician Jonathan Coulton wrote the song entitled "A Talk with George", a part of his 'Thing a Week' series, in tribute to Plimpton's many adventures and approach to life.

Plimpton is the protagonist of the semi-fictional George Plimpton's Video Falconry, a 1983 ColecoVision game postulated by humorist John Hodgman and recreated by video game auteur Tom Fulp.

Researcher and writer Samuel Arbesman filed with NASA to name an asteroid after Plimpton; NASA issued the certificate 7932 Plimpton in 2009. His final interview appeared in The New York Sports Express of October 2, 2003, by journalist Dave Hollander.

Author: Letters in Training (letters to home from Italy, privately printed, 1946); The Rabbit's Umbrella (children's book, 1955) Out of My League (baseball, 1961) Go Caroline, (about Caroline Kennedy, privately printed, 1963) Paper Lion (about his experience playing professional football with the Detroit Lions, 1966) The Bogey Man (about his experiences travelling with the PGA Tour, 1967) Mad Ducks and Bears (about Detroit Lions linemen Alex Karras and John Gordy, with extensive chapters focused on Hall of Fame quarterback Bobby Layne and Plimpton's return to football, this time with the Baltimore Colts, 1973) One for the Record: The Inside Story of Hank Aaron's Chase for the Home Run Record (1974) Shadow Box (about boxing, author's bout with Archie Moore, Ali-Foreman showdown in Zaire, 1977) One More July (about the last NFL training camp of former Packer and future coach Bill Curry, 1977) Fireworks: A History and Celebration (1984) Open Net (about his experience playing professional ice hockey with the Boston Bruins, 1985) The Curious Case of Sidd Finch (a novel that extends a Sports Illustrated April Fools piece about a fictitious baseball pitcher who could throw at over 160 mph (260 km/h), 1987) The X Factor: A Quest for Excellence (1990) The Best of Plimpton (1990) Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career (1997) The Man in the Flying Lawn Chair: And Other Excursions and Observations (2004)

Editor Writers at Work (The Paris Review Interviews), several volumes American Journey: the Times of Robert Kennedy (with Jean Stein) As Told at the Explorers Club: More Than Fifty Gripping Tales of Adventure Edie: An American Girl.

Introductions The Writer's Chapbook: A Compendium of Fact, Opinion, Wit, and Advice from the 20th Century's Preeminent Writers Above New York, by Robert Cameron

Film appearances Lawrence of Arabia (1962) – Bedouin (uncredited) Beyond the Law (1968) – Mayor Hickory Hill (1968) – narrator in Richard Leacock's documentary on the Annual Spring Pet Show at Robert F. Kennedy's Virginia estate, Hickory Hill (McLean, Virginia) The Detective (1968) – Reporter (uncredited) Paper Lion (1968) – Plimpton, played by Alan Alda, is the lead character in the largely fictional film, loosely based on the 1966 nonfiction book. Anecdotally, Plimpton appeared in the film in an uncredited cameo in a crowd scene. Rio Lobo (1970) – 4th Gunman (Plimpton's preparation and filming for his role as "Fourth Gunman" was the subject of a 1972 television program.) The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977) – Quentin Reynolds If Ever I See You Again (1978) – Lawrence Lawrence Reds (1981) – Horace Whigham Garbo Talks (1984) – Himself (uncredited) Volunteers (1985) – Lawrence Bourne Jr. A Fool and His Money (1989) – God Easy Wheels (1989) – Surgeon The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) – Well Wisher L.A. Story (1991) – Straight Weatherman Little Man Tate (1991) – Winston F. Buckner Ken Burns' Baseball (1994) – Himself Just Cause (1995) – Elder Phillips Nixon (1995) – President's Lawyer When We Were Kings (1996) – Himself – Writer Good Will Hunting (Miramax, 1997) – Henry Lipkin – Psychologist The Last Days of Disco (1998) – Clubgoer EDtv (1999) – Panel Member Just Visiting (2001) – Dr. Brady Sam the Man (2001) – Himself The Sports Pages (2001) – Himself The Devil and Daniel Webster (2003) – Himself (uncredited) Factory Girl (2006) – Himself Soul Power (2008) – Himself Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself (2012) – Himself

Television appearances Plimpton! The Man on the Flying Trapeze (1971) – Himself – ABC documentary Mouseterpiece Theater (1983–1984) – Host / Himself – Disney Channel Uncensored Channels: TV Around the World with George Plimpton (1986) The Equalizer (1989) – Clinton Brandauer – Episode: "Starfire" The Civil War (1990) – New Yorker, George Templeton Strong (voice) – Reading his diary Wings (1994) – Dr. Grayson – Episode: "The Shrink" Baseball: A Film by Ken Burns (1994) – (voice) – PBS documentary Married... with Children (1995) – 200the Episode Special Host – Episode: "Best O' Bundy" ER (1998, 2001) – John Truman Carter Sr. Saturday Night Live (1999, 2002) – Himself (uncredited) – Season 1, March 13 episode, he is one of the audience cutaway shots (usually featured in the early seasons with comedic and fictitious non-sequitur captions as to who the audience member was, or what they did). He is labelled as having "Roomed with Wendy Yoshimura". Just Shoot Me (2000) – Himself – During the show's A&E Biography of fictional character 'Nina Van Horn' A Nero Wolfe Mystery (2001–2002) – (various roles) – Member of the repertory cast, in the episodes, "Eeny Meeny Murder Mo", "Over My Dead Body", "Death of a Doxy", "Murder Is Corny", "Help Wanted, Male", "The Silent Speaker" and "Immune to Murder" The Simpsons (2003) – Himself – Episode: "I'm Spelling as Fast as I Can"

Commercial appearances on television Oldsmobile Vista Cruiser, pitchman, himself, released by Oldsmobile in late 1968 for the 1969 model year Intellivision, pitchman, himself, released by Mattel in 1980. Plimpton was featured in a string of Intellivision commercials and print ads in the early 1980s. "Pop-Secret", pitchman, himself.

Literary characterizations Plimpton appears as a character in Philip Roth's novel, Exit Ghost.

Szukasz ciekawej lektury o piłkarskich wydarzeniach z ostatnich miesięcy? Sprawdź https://football-talk.co.uk/226139/football-events-december-month-review/ Artykuł w przystępny sposób przedstawia najważniejsze momenty grudnia w futbolu, oferując świeże spojrzenie i sporo interesujących informacji. Gorąco polecam!

Jeśli interesuje Cię, jak wygląda edukacja za granicą, polecam artykuł czym różni się szkoła w anglii od szkoły w polsce – naprawdę warto to przeczytać! ✨ Dowiesz się , że w Anglii program nauczania jest bardziej elastyczny, uczniowie mają większy wybór przedmiotów i indywidualne podejście do nauki, a w Polsce edukacja opiera się na szerokim, ujednoliconym programie ogólnym. 📚 Każdy system ma swoje zalety, ale różnice są naprawdę fascynujące!